The

Impetus of Ideas

David Banach

St. Anselm College

The

everlasting universe of things

Flows through the mind, and rolls in

rapid waves,

Now dark -- now glittering -- now

reflecting gloom --

Now lending splendour, where from secret

springs

The source of human thought its tributes

brings

.........................................

The

secret strength of things

Which governs thought, and to the

infinite dome

Of heaven is as a law, inhabits thee!

P.

B. Shelley, Mont Blanc

I

would willingly establish it as a general maxim in

the

science of human nature, that when any impression

becomes

present to us, it not only transports the mind to

such

ideas as are related to it, but likewise communicates

to

them a share of its force and vivacity.

David

Hume, A Treatise of Human Nature

I. Lessons from Hume: Hume,

through his masterful criticisms of the ideas of substance, identity, and

causality based upon the principles of empiricism, is thought to have shown us

the limitations of the very empirical principles he employed. His main role the

history of philosophy is to have woken Kant from his dogmatic slumber to remedy

the deficiencies of empiricism.

A.

Hume on Ideas, Impressions, and Beliefs.

1. Ideas are paler copies of sense

impressions differing only from them in their degree of force and vivacity.

Ideas of memory and imagination, likewise, differ only in their vivacity.

Quotes 1, 2, 6.

2. Belief is a habit associated with an idea. This habit is manifested

in the force and vivacity with which the idea is held. Quotes 3,

6, 8.

B.

Hume on general, abstract, ideas:

1.

All ideas are particular and determinate. Ideas became general by bringing to

mind an indefinite number of other ideas according to a custom of habit

associated with the word or idea.

2. The meaning of a general idea,

then, is the custom or habit by which it comes indifferently to bring to mind a

wide range of associated ideas.

3. This custom and the impetus

associated with a general idea are mysterious things to be known by analogy to

other cases: Quote 4.

a. Ideas of large numbers, such

as 1000, do not have a clear and determinate image.

b. An entire verse of poetry,

though we can't recall it at the moment, can be brought back to us in a moment

by one word.

c. We have no clear image for

our complex ideas, such as church, negotiation, or conquest.

d. Knowing and idea bestows a

marvelous ability to bring up relevant ideas at appropriate times without

having a clear idea how we do so. Quote 5.

C. Summary of Hume's insights:

1.

Apart from the representational content of an idea there is another component:

its force and vivacity, its impetus.

2. The impetus of ideas is felt, part of the phenomenology of the

idea, though it is distinct from the content of the idea and is not itself

another idea. (Indeed, it would have been more consistent for Hume to consider

emotions and sentiments as these types of impetüs than as separate ideas.)

3. The impetus of ideas, as the name

suggests, is active, is connected

with habit or custom, and directs the production and flow of ideas. Quote 8

4. Since the meaning of general

ideas is a custom, the un-represented

meaning of an idea is its impetus, which is distinct from its definition, or

list of instances, or explicit rules for producing these instances.

II. Applications: These insights of Hume's reminded me of two

elements of my own thought, as influenced by Alfred North Whitehead:

A. Representing as connection of modes of interaction with the world. Acts of representing are self-justifying through their phenomenological feel.

1. The Problem of the Representational Model of Knowledge. Figures 1-2.

2. The problem solved: While the particular modes of interaction in our acts of representing cannot be objective and represent the world, the connection between these modes that we find within our representings can be objective. The world either reinforces or diminishes the connections we make within our acts of perceptual representing, and this manifests itself in the phenomenological feel (the force and vivacity) of our representation. On the view I am suggesting, particular images or effects the object has on us are not representations. A representation is a process of connecting two such effects, and its content lies in this connection, not in the particular features of the images connected. The content of my perception of the rose as red and as fragrant is not the "feel" of these particular images, but the connections that are established between them by my act of representing. While the particular features of the images reflect only the effect the object has on me, the connections within my representation can reflect the connections between the real dispositions in the object that give rise to these effects. While there is no determinate isomorphism between individual icons and the world, there can be an isomorphism between the connections made between modes of interaction within an act of representing and the properties in the object that participated in the modes of interaction that are connected. Connections can be objective while images cannot. Figure 3.

B. Expression, Imagination, and Poetic Language: Ideas and symbols mean in two different ways, which might be almost thought to correspond to the distinction between natural and conventional signs. The first is the representation or the determinate idea. The second is the impetus of the idea.

1. Their explicit literal content according to conventional associations and rules. This is the literal meaning of an idea, as expressed by prose and its syntax and semantics. It is very clear and distinct; its clarity and distinctness being provided by the operations of the understanding. This corresponds to Whitehead's perception in the mode of presentational immediacy, and much the same distinction can be made between our different modes of perception as well. Conceptual understanding controls this type of perception and meaning, and it forms the foundation of theoretical prose. It operates according to the imposed rules and constraints of the understanding.

2. A vague complex of feelings and associations, that precedes guides and impels the concrete expressions of the idea. These are the impetüs referred to in Hume's four examples. These are the felt forces, habits ,and dispositions that are always necessary to explain how representation really works: to explain how general representation works and to explain the nature of form in the mind. We have a vague feeling of the intent of our actions and our expressions before we perform them, and this vague feeling impels and guides our activity of expression. (Comparisons to Aristotle's connection of essential form and final causation, of potency and act, are not misplaced here.) This is analogous to Whitehead's perception in the mode of casual efficacy, our vague perception of the past states of our body and the world that contributes the underlying feel to our perceptions. The poet uses language in a different way to allow it to produce in the mind these vague feelings that lie at the root of language and thought. Poetic language causes its effect through its form; it does not signify it through its syntax and semantics.

III. Problems and proposed solutions: These applications of Hume's insights can be extended further to solve two fundamental problems in the philosophy of perception and cognition:

A. The problems:

1. Given what we know about perception, it seems impossible that the content of our perceptions (secondary properties) can really be a reflection of the object. How are objects and their properties carried up our optic nerve and recreated in our brain-mind.

2. How is the content of our perceptions caused by reality. While it seems clear that there is a causal chain from the object to our act of perceiving it, the more we know of this causal chain the less likely it seems that the peculiar qualities of experience can be caused by the world.

B. Two proposals using and modifying Hume's insights.

1. Impetüs are un-represented ideas (representations). They provide the (unformed) content which will be channeled and formed in the act of representing. Hume took them to be separate from the content, while at the same time considering them to be the force and vivacity of that content. I propose that these impetüs have content; they guide and impel our ideas and their development. I propose further that in fact they are the content which will be re-presented, guided, channeled, and formed by their projection onto a medium of representation. In my terminology, they are the indeterminate content of the modes of interaction that are connected in an act of representing. They are the presented content that is re-presented in an act of representation.

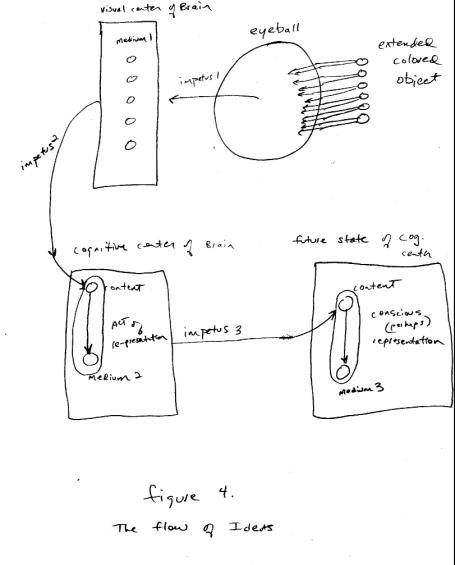

2. While the content of representations as re-presented is not caused by the object, the impetus is so caused. An impetus is formal. It is the form of the felt force of the connection between different modes of interaction with the world. Such forms are capable of being, and in fact are, transmitted through the causal operations of the sense organs and nervous system. (Figure 4.) These forms, which flow to us from their secret source within things are then channeled and re-transmitted in the many stages of re-presentation that lead to conscious perception. The imagination is precisely the faculty of performing the connections of past and present forms that transmits (and in the free operation of the imagination, creates) this impetus, the impetus of our ideas. Hence, the everlasting universe of things is indeed flowing through us with the transmission and channeling of an impetus. And since an impetus originates in an impression and transmits the form of the object, the secret strength of things, which governs thought, and to the infinite dome of heaven is as a law, does indeed inhabit thee.

Quotes from A Treatise of Human Nature

All quotes from Book I, Part I.

From SECT. 1.

Quote

1: Impressions and Ideas.

ALL the perceptions of the human mind resolve

themselves into two distinct kinds, which I shall call

IMPRESSIONS and IDEAS. The difference betwixt these consists

in the degrees of force and liveliness, with which they

strike upon the mind, and make their way into our thought or

consciousness. Those perceptions, which enter with most

force and violence, we may name impressions: and under this

name I comprehend all our sensations, passions and emotions,

as they make their first appearance in the soul.

Quote

2: Impressions and ideas differ not in content but only in impetus

The first circumstance, that strikes my eye, is

the great resemblance betwixt our impressions and ideas in

every other particular, except their degree of force and

vivacity.

From SECT. V.-Of the Impressions of the Senses and Memory.

Thus it appears, that the belief or assent, which

always attends the memory and senses, is nothing but the

vivacity of those perceptions they present; and that this

alone distinguishes them from the imagination. To believe is

in this case to feel an immediate impression of the senses,

or a {1:387} repetition of that impression in the memory.

'Tis merely the force and liveliness of the perception,

which constitutes the first act of the judgment, and lays

the foundation of that reasoning, which we build upon it,

when we trace the relation of cause and effect.

From SECT. VII. Of Abstract Ideas.

Quote

4: Meaning of general idea a custom

A particular idea becomes general by being

annex'd to a general term; that is, to a term, which from a

customary conjunction has a relation to many other

particular ideas, and readily recalls them in the

imagination.

The only difficulty, that can remain on this subject,

must be with regard to that custom, which so readily

recalls every particular idea, for which we may have

occasion, and is excited by any word or sound, to which we

commonly annex it. The most proper method, in my opinion,

of giving a satisfactory explication of this act of the

mind, is by producing other instances, which are analogous

to it, and other principles, which facilitate its

operation. To explain the ultimate causes of our mental

actions is impossible. 'Tis sufficient, if we can give any

satisfactory account of them from experience and analogy.

Quote

5: Custom or impetus a mysterious power of the soul

The fancy runs from one end of

the universe to the other in collecting those ideas, which

belong to any subject. One would think the whole

intellectual world of ideas was at once subjected to our

view, and that we did nothing but pick out such as were most

proper for our purpose. There may not, however, be any

present, beside those very ideas, that are thus collected by

a kind of magical faculty in the soul, which, tho' it be

always most perfect in the greatest geniuses, and is

properly what we call a genius, is however inexplicable by

the utmost efforts of human understanding.

From SECT. VII.-OF the Nature of the Idea or Belief.

Quote

6: Impetus does not change content. Belief an impetus

All the perceptions of the mind are of two kinds, viz.

impressions and ideas, which differ from each other only in

their different degrees of force and vivacity.' Our ideas

are copy'd from our impressions, and represent them in all

their parts. When you would any way vary the idea of a

particular object, you can only increase or diminish its

force and vivacity. If you make any other change on it, it

represents a different object or impression. The case is the

same as in colours. A particular shade of any colour may

acquire a new degree of liveliness or brightness without any

other variation. But when you produce any other variation,

'tis no longer the same shade or colour. So that as belief

does nothing but vary the manner, in which we conceive any

object, it can only bestow on our ideas an additional force

and vivacity. An opinion, therefore, or belief may be

most, accurately defined, A LIVELY IDEA RELATED TO OR

ASSOCIATED WITH A PRESENT IMPRESSION.

Quote 7: Impetus

something felt but mysterious.

An idea assented to <feels> different

from a fictitious idea, that the fancy alone presents to us:

And this different feeling I endeavour to explain by calling

it a superior force, or vivacity, or solidity, or

<firmness>, or steadiness. This variety of terms, which may

seem so unphilosophical, is intended only to express that

act of the mind, which renders realities more present to us

than fictions, causes them to weigh more in the thought, and

gives them a superior influence on the passions and

imagination.

...........................

I confess, that 'tis impossible to

explain perfectly this feeling or manner of conception. We

may make use of words, that express something near it. But

its true and proper name is belief, which is a term that

every one sufficiently understands in common life.

From SECT. VIII.-OF the Causes of Belief.

Quote 8: Impetus transmitted from idea to idea,

originates in object.

I would willingly establish it as a general maxim in

the science of human nature, that when any impression

becomes present to us, it not only transports the mind to

such ideas as are related to it, but likewise communicates

to them a share of its force and vivacity.

Now 'tis evident the

continuance of the disposition depends entirely on the

objects, about which the mind is employ'd; and that any new

object naturally gives a new direction to the spirits, and

changes the disposition; as on the contrary, when the mind

fixes constantly on the same object, or passes easily and

insensibly along related objects, the disposition has a much

longer duration.

Figures

Figure 1: The Representational Model of Knowledge.

Figure 2: The Problem with the Model

Figure 3: Representation as an act of connecting modes of interaction (impetus)

Figure 4: The Flow of Ideas