SECOND YEAR - SECOND SEMESTER

Unit 11 – Sartre

1/91

Lecture 2

The Ethics of Absolute Freedom

David Banach

I.

Individuality,

Freedom, and Ethics.

The modern conception of man is

characterized, more than anything else, by individualism.

Existentialism can be seen as a rigorous

attempt to work out the implications of this individualism.

The purpose of this lecture is to makes

sense of the Existentialist conception of individuality and the

answers it

gives to these three questions: (1) What is human freedom? What can

the

absolute freedom of absolute individuals mean? (2) What is human

flourishing or

human happiness? What general ethic or way of life emerges when we

take our

individuality seriously? (3) What ought we to do? What ethics or code

of action

can emerge from a position that takes our individuality seriously. Although I am sure you will

want to take a

critical look at the assumptions from which Existentialism arises in

your

seminars, I will be attempting, sympathetically, to see what follows

if one

takes these assumptions seriously.

Let's begin by seeing what it could

mean to say we are absolute individuals.

When you think of it, each of us is alone in the world.

Only we feel our pains, our pleasures, our

hopes, and our fears immediately, subjectively, from the inside. Other people only see us

from the outside,

objectively, and, hard as we may try, we can only see them from the

outside. No one else can

feel what we

feel, and we cannot feel what is going on in any one else's mind.

Actually,

when you think of it, the only

thing we ever perceive immediately and directly is ourselves and the

images and

experiences in our mind. When

we look

at another person or object, we don't see it directly as it is; we see

it only

as it is represented in our own experience.

When you feel the seat under your rear-end, do you really feel

the seat

itself or do you merely feel the sensations transmitted to you by

nerve endings

in your posterior?. When

you look at

the person next to you (contemplating how their rear-end feels), do

you really

see them as they are on the inside or feel what they feel? You see

only the

image of them that is presented to your mind through your senses. This is easily demonstrated

by considering

how our senses deceive us in optical illusions, but one simple example

will

have to suffice here. [split

image

demonstration] It seems, then, that we are minds trapped in bodies,

only

perceiving the images transmitted to us through our bodies and their

senses.

Each of us is trapped within our own

mind, unable to feel anything but our own feelings and experiences. It is as if each of us is

trapped in a dark

room with no windows. Our

only access to

the outside world being a television screen on one wall on which we

(with our mind's

eye) perceive the images of other people, places, and things.

Thus, to be an absolute individual is to be

trapped within ourselves, unable to perceive or contact anything but

the images

on our mental tv screen, and to be imperceptible ourselves to anyone

outside of

us. In a world where

science has opened

up and laid bare the nature of subatomic particles, far-away planets,

and the

workings of our very own bodies and brains, it is to remain,

ourselves, hidden

from the objective view. It

is to be an

island of subjectivity in an otherwise objective world.

II. The Existentialist View of

Human

Freedom.

What view of human nature can emerge

from this view of the individual? One such view is the view of human

nature

identified with the name Existentialism.

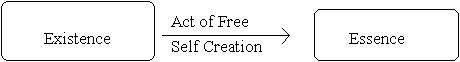

Sartre says that what all existentialists, both atheistic and

christian,

share in common "... is that they think that existence precedes

essence,

or, if you prefer, that subjectivity must be the starting point."

(EHE, p.

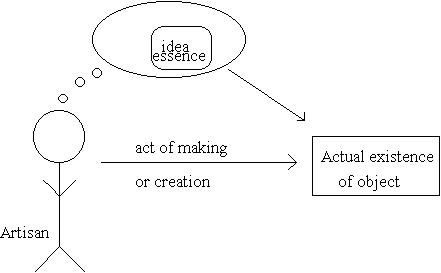

13) Sartre explains what this means by contrasting it with the

opposite slogan:

ESSENCE PRECEDES EXISTENCE. He

uses the

example of a paper-cutter to explain how the old view treated human

beings as

artifacts, whose nature is tied to a preconceived essence and to a

project

outside of them, rather than as absolute individuals. He says in Existentialism and Human Emotions:

Let

us consider some object that is manufactured, for example, a

book or a paper-cutter: here is an object which has been made by an

artisan

whose inspiration came from a concept.

He referred to the concept of what a paper-cutter is ... . Thus, the paper-cutter is

at once an object

produced in a certain way and, on the other hand, one having a

specific use ...

. Therefore, let us say

that, for the

paper-cutter, essence ... precedes existence. (EHE, pp. 13-14)

Of

course,

the artisan in our case is God.

Sartre

continues:

When

we conceive of God as the Creator, He is generally thought of as a

superior

sort of artisan. ...

Thus the concept

of man in the mind of God is comparable to the concept of the

paper-cutter in

the mind of the manufacturer... .

Thus,

the individual man is the realization of a certain concept in the

divine

intelligence. (EHE, p. 14)

On

this

view, the one Sartre is attacking, we get our nature from outside of

us, from a

being who created us with a preconceived idea of what we were to be

and what we

were to be good for. Our

happiness and

our fulfillment consist in our living up to the external standards

that God had

in mind in creating us. Both

our nature

and our value come from outside of us.

According to the existentialist,

however, EXISTENCE PRECEDES ESSENCE.

Sartre explains:

What

is meant here by saying that existence precedes essence? It

means that first of all, man exists, turns up, appears on the scene,

and, only

afterwards, defines himself. ...

Not

only is man what he conceives himself to be, but he is also only what

he wills

himself to be after this thrust toward existence.

Man is nothing else

but

what he makes of himself. (EHE, p. 15)

Thus,

there

is no human nature which provides us with an external source of

determination

and value. Sartre says:

If

existence really does precede essence, there is no explaining

things away by reference to a fixed and given human nature.

In other words, there is no determinism, man

is free, man is freedom.

Nothing

outside

of us can determine what we are and what we are good for; we must do

it

ourselves, from the inside. What

we

will be and what will be good for us is a radically individual matter.

If we

are radical individuals, there is no place else for our nature and

value to

come from, except from within us.

It is

this view of human nature, or the lack thereof, from which the

existentialist

conceptions of freedom and value flow.

We are now in a position to begin to answer the first of our

three

main questions: What is human freedom? What, exactly can the freedom

of an

absolute individual consist of? At first, it may seem clear that if we

are

islands of subjectivity, isolated from the forces of the outside

world, we not

only are capable of acting freely of outside determination, but we

cannot help

doing so since the only possible sources of action are internal. The situation, however, is

somewhat more

complex than this. To

understand what

freedom is for the Existentialist we must first see how, even though

our

inescapable nature is to be free, we all inevitably tend to try to

escape our

freedom. We all tend to

act in what

Sartre calls 'bad faith'. We

attempt to

deceive ourselves and act as if we weren't free, as if we were really

determined by our nature, our body, or the expectations of other

people.

The picture we drew earlier of the

human individual trapped in a dark room perceiving the world only

through our

mental TV screens was too simple, for humans have a dual nature. Among the things we find on

the mental tv

screen, besides objects, other people, emotions, and desires, is

ourselves. I see my

body, and this

thing I see is me. The

human condition,

for the Existentialist is a tension, a vertiginous imbalance, between

the self

that watches these images, standing apart from them, and the self that

appears

as an image. Just as I

feel an

imbalance upon walking into a department store and finding that one of

the

people on the video monitor is ME (caught by some unseen camera); or

just as we

feel a tension looking in the mirror wondering how the person in the

glass can

be ME if I am standing out here looking at it; so the self feels a

tension

between identifying itself with mind's eye behind the screen (standing

apart

from the give and take, the flux and flow, of our experience) and the

images of

us that appear as part of our experience (engaged in the world).

Thus, we all have the tendency to

act in bad faith, to identify ourselves with one of the pictures we

find on our

mental TV screen, and to see ourselves as determined by one of the

outside

influences we find pictured there: our nature, our body, the physical

world, or

the expectations and pictures other people have of us.

We are all familiar with the ways in which

we try to excuse our actions by pretending that we are simply our

bodies and

are controlled by the forces that determine them. We have all said things like:

I

can't talk to people, I just don't have that kind of

personality.

I

can't pass this course, I'm just don't have the brain for

calculus.

I

can't help the fact that I was born a man (or a woman); Certain

things come naturally for certain types of people. (Says the man who can't take care of his children, or the

woman

who can't fix her car.)

I'm

no good at this; I guess I just wasn't made to go to college.

Gee,

I'm sorry about last night.

I guess my hormones just got out of control.

I'm

sorry I bit your head off yesterday. I must be premenstrual.

I

don't know what happened.

I guess the beer made me crazy.

In

these

cases, I am identifying myself with one of the pictures of me I find

on my

mental TV screen: I am my body, or my brain, or my personality, or my

hormones. In each of

these cases, I am

deceiving myself. I am

more than just

these, and no matter how I try to avoid it, I am free.

We are

also familiar with the way we all

play roles, identifying ourselves, or seeing ourselves, in terms of

how other

people see us, letting other people determine what we are instead of

deciding,

ourselves, what we will be. We

all to

some extent tend to make ourselves into the image other people have of

us. We are a different

person with our friends

than with our parents. We are a different person with a lover than

with our

acquaintances, and we are different still when we are in the classroom

or at a

job interview. It is

often easier to

let someone else determine what we will be than to do it ourselves,

especially

when we see our value in terms of the acceptance we get from other

people. We all see

little pictures of ourselves

projected by other people and we often tend to try to make ourselves

into these

little pictures by playing roles.

We

play at being college students out for a good time, at being macho men

or

nurturing women, at being sons or daughters, at being businesswomen,

policemen,

scientists. We play at

being students

taking notes, and professors giving lectures.

We play the roles; we make ourselves into characters in the

plays; we

make ourselves into little pictures on our mental tv screen determined

by the

script written by the expectations of other people.

But all of this is

self-deception. We are

more than any of

the pictures we find on our mental tv screen.

We stand behind it, watching it, making of it what we will. It is impossible to

abdicate our

freedom. In choosing to

identify

ourselves with some externally determined object we are choosing none

the less.

We cannot escape our freedom.

One might well ask at this point,

"What does this freedom consist of.

Am I free to become George Bush right now? Am I free to become

a woman

(without some fairly extensive and unpleasant surgery)? Am I free to

fly up to

the ceiling and hover above your heads? Am I free to close my eyes

right now

and find myself in the Bahamas when I reopen them? Unfortunately,it appears not. How, then, can I be free when

most

of my external circumstances are determined by forces beyond my

control, when I

cannot help where I was born, what type of body I have, and what type

of

abilities my brain has predisposed me towards?"

The answer to these questions lies

in the nature of our radical individuality.

I am not identical with any of the externally determined images

on my

mental TV screen. I am

forever beyond

the reach of their determinations within the island of my

subjectivity.[1] Even if I were a puppet, my

body and its

actions completely controlled by some malevolent master, what I am, my

mind's

eye would still be free and untouched.

I could still be free to rebel against my master or make

whatever I

wished of the situation. They

can do

what they want to my body, manipulate the objects or pictures of me on

my

mental TV screen, but they can never touch or control the real me. The self within its island

of subjectivity

is radically free in virtue of its radical individuality.

Furthermore, I have control over the

content of my TV screen as well.

External circumstances may determine the objects that appear,

how they

appear, and when they appear, but I control how these various

components will

be put together into a coherent picture.

Sartre compares the type of freedom we have to that of an

artist (EHE,

pp. 42-43). An artist

cannot control

the nature of the canvas, nor of the paints that she has to work with. Nor can she control the

nature of the

subjects she will paint. But

she can

control how she will view them, how she will put these various

elements

together into a unique whole. Likewise,

we

may not be able to control the various elements within our experience

that

come from outside us, but we can view them and combine them in any way

we

like. Our experience is

not any one of

these; it is the way in which we combine these into a unified whole. We have the power to edit

the frames which

constitute our experience into the film that is to be our life.

We all know the power of good editing, of

the creative juxtaposition of determinate elements. It can transform experience; make the ugly beautiful and the

ordinary, sublime.

Our freedom is, thus, a freedom of

synthesis. It is the

freedom to pull

ourselves together into the type of coherent whole that we will

ourselves to

be. Even if the raw

materials from

which we construct ourselves are determined (just as the materials of

the

artist are determined), what

we make of

ourselves out of these materials is up to us alone (just as what the

artist

makes of her subject is up to her alone).

We can not make the external world determine this even if we

try. The sentence of

freedom is the necessity of

pulling ourselves together at each moment out of the myriad different

influences imposing themselves upon us from the environment, our

community,and

from our own bodies. We

are required to

make ourselves, to pull ourselves together, and we can make of

ourselves what

we will.

The answer to our first question is,

then, that we can be free because (1) Our absolute individuality

isolates our

real self from the determining influences of the outside world; we can

always

rebel against its influence; and (2) Even though the raw material that

makes up

our experience is determined by outside influences we are free to put

these

elements together into a unified whole; we must make ourselves anew at

each

moment, and what we shall make of ourselves is up to us.

We now need to see what view of human

happiness and of morality arise from this conception of human freedom. Both of these can be summed

up by the single

slogan BE AUTHENTIC. The

secret of

human flourishing and of moral action lies in avoiding bad faith and

honoring

the responsibility we have to create our own nature and values.

The Existentialist enjoins us to be

ourselves and make the source of our nature and values our own

internal

decisions rather than the pictures of ourselves that appear in our

minds from

external sources. Let us

now see what

view of human happiness this implies.

III. The Existentialist View of

Human

Happiness.

Existentialism is often associated

with such themes as the absurdity of human existence and the

worthlessness of our

lives given our inevitable death.

One

might well wonder what view of happiness could arise from such a view. Sartre characterizes the

human condition by

(1) our forlorness at the loss of external values and determinants of

our

nature; (2) anguish at the resultant responsibility to create human

nature

ourselves; and (3) despair of finding value outside of ourselves and

reliance

upon what is under our own control.

Forlorness, anguish, and despair: Mr. Sartre, it would seem,

was not a

happy camper. For

another 20th century

French existentialist philosopher Albert Camus, however, the loss of

any

external source of value did not present quite such a dismal prospect.[2]

Camus compares our situation to that

of the mythical figure Sisyphus.

In his

essay "The Myth of Sisyphus" he explains that:

The

Gods had condemned Sisyphus to ceaselessly rolling a rock to

the top of a mountain, whence the stone would fall back of its own

weight. They had thought

with some reason that there

is no more dreadful punishment than futile and hopeless labor. (MS, p.

88)

It

is easy

to see the similarity between this situation and ours according to the

Existentialist. Just as

Sisyphus can

find no end to his activities, no final resting place where he has

finally

reached his goal or lived up to some set of pre-existing standards, so

we find

that all of our activities lead to nowhere. There are no external

values that

we can live up to, no external viewpoint from which our life can be

viewed to

be valuable. Our life is

a series of meaningless

actions culminating in death, with no possibility of external

justification. Yet,

Camus will say that

we must imagine Sisyphus (and ourselves) happy? "One must imagine Sisyphus happy." (MS, p. 91)

Why?

Why would this fool be happy eternally rolling a ball up a

hill, and why

should we be happy rolling our ball up the hill to nowhere?

At first, when one was still

expecting to get ones value from outside of oneself, all this might

seem

depressing. Camus says:

When

images of the earth cling to tightly to memory, when the call

of happiness becomes to insistent, it happens that melancholy rises in

man's

heart:this is the rock's victory this is the rock itself.

The boundless grief is to heavy to bear.

These are our nights in Gethsemane.

But crushing truths perish from being

acknowledged.

..............................................

Sisyphus,

proletarian of the gods, powerless and rebellious, knows

the whole extent of his wretched condition: it is what he thinks of

during his

descent. The lucidity

that was to

constitute his torture at the same time crowns his victory.There is no

fate

that cannot be surmounted by scorn.

(MS,

p. 90)

As

we saw

before, no matter what his external circumstances, Sisyphus is always

free to

make of them what he will, to rebel

against them within his island of subjectivity.

No matter what the Gods make him do, he is

always free to give the Gods one of these [defiant gesture].

I remember when I first read this

(as a senior in high school) thinking that this was sort of a stupid

response

to the absurdity of the human condition.

What sense does it make to give one of these [defiant gesture]

to a

non-existent God whose absence is the source of the absurdity of our

lives. What are we

rebelling against? There must be

more to the existentialist conception of happiness than this, I

thought.

And there was. The despair

and rebellion we feel at the loss of our external sources of value are

the

necessary price of a greater value and happiness that comes from

within. One must lose

all hope of external value

before seeking value within. The

theme

that true happiness must come from within is one that is familiar to

all of us,

and it is the key to understanding the existentialist conception of

happiness.

Two contemporary folk tails embody

this existentialist theme well: The Wizard of Oz and How the Grinch

Stole

Christmas. This common

theme probably

does not show that these are existentialist works, but only that the

American

emphasis on self-reliance and internalism flows from the same

individualist

emphasis as Existentialism. In

the

Wizard of Oz there is an external realm, somewhere over the rainbow,

where

everything is as it should be and all problems are solved.

There is a wizard who will give us brains, a

heart, courage, and happiness. When

Dorothy

got there and discovered that Oz was full of the same type of evil as

Kansas, when they discovered that the Wizard was a hoax, that there

was nothing

outside of them that was going to make them what they wanted to be,

they were

understandably depressed. But

this

disappointment was the necessary price of an important lesson: that

the only

place they could get a brain, or a heart, or courage was from within. Dorothy learns that if she

ever loses

anything that cannot be found within her own back yard, it wasn't

really lost

at all. There is no

place like Home.

(Especially if you are an island of subjectivity, for then there is no

place

but home.) The value one gets from within is infinitely better than

the value

one vainly attempts to get from outside.

The story of the Grinch shows why

this is so. At first

when the Who's in

Whoville woke up to find that the Grinch had stolen their Bamboozlers

and

Dingdangers, they were at first very disappointed. They thought that the value of Christmas was in these

external

things. What they

discovered, and what

the grinch discovered looking out over Whoville listening for sounds

of grief

and hearing, instead, the sounds of joy, was that their real value

came from

within and was greater than any value that could come from external

things

since it couldn't be taken away.

A common

theme in existentialist

literature is the transformation that can occur in one's outlook on

life when

one is forced to face death. One

of the

founders of Existentialism, the 19th century Russian novelist Fyodor

Dostoevsky, actually had such a brush with death transform his life. He was involved in some

activities that ran

afoul of the Czar and was among the people rounded up in one of the

Czar's

crackdowns. He was told

that he would

be executed. He was

blindfolded and

made to wait his turn to face death.

At

the last minute, as Dostoevsky prepared to meet death, he got a

reprieve. It turned out

that he was to be sent to a

labor camp instead and that this had merely been a cruel joke.

One might imagine that if one could face

one's death, face the impossibility of getting any value from any

external

accomplishments, and still find value within oneself, that value would

be invulnerable. It

could never be taken away. What else

could they do to you?

If, after all sources of external

value have been taken away, you can find value within yourself, you

would have

found what philosophers have been looking for throughout the ages: a

way of

achieving human happiness that is not vulnerable to the uncontrollable

contingencies of the natural world.

If

we find ourselves isolated from external value by our radical

individuality, we

can make a world of ourselves, a universe of our own experience, in

which we

can and must find ourselves happy.

Camus writes of Sisyphus:

The

absurd man says yes and his effort will henceforth be

unceasing. ... he knows

himself to be

the master of his days. At

that subtle

moment when man glances backward over his life, Sisyphus returning

toward his

rock, in that slight pivoting he contemplates that series of unrelated

actions

which becomes his fate, created by him, combined under his memory's

eye and

soon sealed by his death.

............................................

But

Sisyphus teaches a higher fidelity that negates the gods and

raises rocks. He too

concludes that all

is well. This universe

henceforth

without a master seems to him neither sterile nor futile.

Each atom of that stone, each mineral flake

of that night-filled mountain, in itself forms a world.

The struggle itself toward the heights is

enough to fill a man's heart. One

must

imagine Sisyphus happy. (MS, p.91)

The

Existentialist's secret of happiness,

then, is to get ones

value from within

oneself. In doing so,

one loses the

promise of external value, but they find a more real happiness, one

that cannot

be taken away by the external forces beyond their control.

IV. The Ethics of Absolute

Freedom.

This

conception of happiness, however, raises

our third question: How ought we act towards other people? If the

source of our

value and nature is wholly internal, what obligations can I have to

other

humans? Can I freely and authentically choose to kill my mother, as

Orestes

does? Can I choose to be a murderer, a thief, or an exploiter of

humanity? Is

it true, as some Existentialist were fond of pointing out, that if God

is dead

then all things are allowable? I'm sure that you will want to discuss

this

issue, as it arises in The Flies, in your seminars, but I would like

to briefly

present you with what I take to be Sartre's three-fold response to

this

question in Existentialism and Human Emotions.

(1)

First, in choosing our own human

nature, according to Sartre, we choose human nature for all humans. Hence, we must choose

courses of action that

we would wish all humans to take. In choosing for ourselves, we choose

for all

men. This must be the

case because, in

order to act freely, I cannot allow myself to be affected by my

peculiar

circumstances, desires, or goals. This would be to act in bad faith,

to try to

identify myself with my desires, or my plans, or my circumstances, and

these

are all merely pictures on my mental TV screen. When I act freely, the only things that can affect my action

must

be things that I share with all free agents.

Thus, I must choose in the same way I would want others to

choose. To say that one

must act authentically is to

say that one must act in a way that ignores the differences between

oneself and

other people. After all,

these

differences are merely external and do not affect our identity as free

agents,

within our islands of subjectivity.

To

be free, then, I must follow the golden rule and act only as I would

have

others act.

(2)

Sartre also argues that in order to

be free, we must desire the freedom of all men. It is self-defeating to attempt to use other humans as

objects to

satisfy our desires, or to protect our freedom at the cost of

enslaving others. If I

attempt to enslave others or use them as

objects, I make myself a slave and an object.

The person who attempts to dominate other people finds himself

a slave

to his dependence on the attention and approval of the people he tries

to

enslave. Think of the

tough guy leader

of a clique of teenagers. He

defines

himself in terms of the expectations of his peers to keep their

approval and

admiration. He makes

himself into a

character controlled by the very slaves of whom he takes himself to be

the

master. The person who

uses other

people as objects to satisfy his desires makes himself an object. He can see other people

only through his

desires, and ultimately sees himself only as his desire.

The manipulator, who attempts to buy and

sell other people for his own ends, finds that he has sold his own

soul as well

by seeing himself merely as his desires.

To see others as slaves of our desire is to make ourselves a

slave of

desire. To be free, we

must desire the

freedom of all men.

(3)

Third, the free decisions that we

make are not merely arbitrary. As

we

saw earlier, freedom does not mean just being able to do anything.

The artist is free to create; she does not follow any explicit

rules. Yet her action is

constrained by

the requirement that her creation must be coherent. In order to be her creation, she must pull the various

disparate

elements that go into the painting into one unified whole.

Her freedom is a freedom of synthesis

constrained by the material she has to work with and the requirement

that she

make some one unified thing out of it.

In the same way, our actions must unify the many different

influences on

our lives into the one life that is to be ours. In pulling ourselves together, we cannot ignore the

relationships

and obligations that provide the raw materials of our lives.

We must weave them into our lives, although

how we will do this is up to us.

Our

actions, though free, are constrained by our situation in a community. Orestes, as you shall see

in The Flies, is

not free to ignore his family, his country, and his mother's crime. Why does he not just leave,

as Zeus

suggests?

The

ethics of absolute freedom, it would

seem, are not absolutely free. To

be

free we must take on the responsibility of choosing for all men, we

must desire

and work for the freedom of all men, and we must create ourselves

within the

context of the relationships and obligations we have to other people.

Is the

ethic of absolute freedom a

portrait of human greatness? Human excellence often defines itself in

the

struggle against the forces that oppose human flourishing.

Existentialism attempts to find happiness,

value, and meaning in a modern world characterized by isolation,

inauthenticity, and absurdity. It

attempts

to see what human excellence can consist of if we find ourselves to be

islands

of subjectivity in an otherwise objective world. You will certainly want to ask if this is in fact what we

find

ourselves to be, but can it be doubted that the Existentialist attempt

to find

meaning in the face of

absurdity

exemplifies the basic drive that all portraits of human excellence

must embody.

References

(MS) Camus, Albert. The Myth of

Sisyphus and

Other Essays (trans. by Justin O'Brien). New York: Vintage, 1955.

(EHE)

Sartre,

Jean-Paul. Existentialism and Human Emotions (Trans. by Bernard

Frechtman). New York: Philosophical Library, 1957.