Berkeley's

Argument and the Perspectivist Fallacy

David

Banach

If you can conceive it possible for one extended

movable substance, or, in general, for any one idea, or anything like an idea,

to exist otherwise than in a mind perceiving it, I shall readily give up the

cause

..................................................

But, say you, surely there is nothing easier than for one to imagine trees, for

instance, in a park, or books existing in a closet, and nobody by to perceive

them. ... but what is all this, I beseech you, more than framing in your mind

certain ideas which you call books and trees, and at the same time omitting to

frame the idea of any one that may perceive them. ... but it does not show that

you can conceive it possible the objects of your thought may exist without the

mind. To make out this, it is necessary that you conceive them existing

unconceived or unthought of, which is a manifest repugnancy. When we do the

utmost to conceive the existence of external bodies we are all the while only

contemplating our own ideas. (George Berkeley, A Treatise Concerning the

Principles of Human Knowledge, I, 22-23: Berkeley 1962, pp. 75-76)

The fact that any conception of a material object is a

representation in the mind does not imply that the object of that conception,

the material object, is also merely an idea in the mind. It is true that any

conception of a material object is an idea in the mind, but it does not follow

from this that the object of that conception is merely in the mind as well.

Conceptions in the mind can be about objects outside of the mind, and it is

commonly thought that Berkeley's argument does not show otherwise. Hence, this

argument, upon which Berkeley is willing to put so much weight, is often

thought to be obviously invalid because it conflates the properties of a

concept with those of the thing the concept represents. I will argue that

Berkeley's argument does not make this mistake and that the argument, while

still fallacious, is more subtle and

powerful than is commonly thought. In

fact, I will argue that it is a form of argument that is common, and

often foundational, in contemporary

thinkers such as Rorty and Putnam, a form of argument I will call the

Perspectivist Fallacy. The purpose of this paper is to show that Berkeley's

argument, properly interpreted, is a strong version of the Perspectivist

Fallacy, to show its similarity to a number of important contemporary

arguments, and to show that all of these arguments are in fact fallacious.

I

The Perspectivist

Fallacy

Before looking directly at

Berkeley's argument, we will need to see exactly what the Perspectivist Fallacy

is and why it is a fallacy. We will then be able to see more clearly how

Berkeley's argument shares the same form as the contemporary arguments of Rorty

and Putnam and how all three are based upon the same error.

The Perspectivist Fallacy is the

argument that representations from particular perspectives cannot be true or

objective, simply because they are perspectival. There is also a stronger

version of the Perspectivist Fallacy which argues that representations from

particular perspectives cannot even refer to or be about objects outside of

that perspective. (This is the version that I shall attribute to Berkeley.)

Before we look at why these types of arguments are fallacies, it will be useful

to look at some examples to see just how prevalent these forms of argument are,

both in common discourse and in contemporary epistemology:

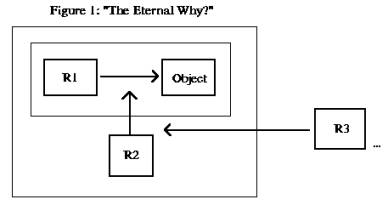

The first and most common of these

The Eternal Why: (Figure 1.) Every representation of reality

is just a representation (R1) and needs further justification. But every

justification is just another representation (R2), which itself needs

justification (R3). In order to determine whether a representation of reality

(R1) is true, we need to represent to ourselves the relation or correspondence

of the representation to the object (R2). But this second representation is

itself merely a representation and its truth must be seen through yet another

representation (R3), and so on.

The five year old's

version:

"Why is the sky blue Daddy? Because different colors of light are absorbed

by the atmosphere to different degrees. But why does air absorb light like that

Daddy? Because it has a certain molecular structure. But why does the structure

absorb light this way Daddy? Because of the nature of light. But why does light

have this nature Daddy? Ask your Mother." Each explanation is merely an

account which does not carry within itself its own justification; hence, the

possibility of a repeated questioning of each account.

Richard Rorty's version: For Rorty, the

representation is language, and philosophy is the attempt to justify our

linguistic statements by elucidating the way in which language relates to the

world. Rorty says in the Preface to Consequences of Pragmatism:

The latter suggestion presupposes that there is

some way of breaking out of language in order to compare it with something

else. But there is no way to think about either the world or our purposes

except by using our language. One can use language to criticize and enlarge

itself, as one can exercise one's body to develop and strengthen and enlarge

it, but one cannot see language-as-a-whole in relation to something else to

which it applies, or for which it is a means to an end. ... Philosophy, the

attempt to say "how language relates to the world" by saying what makes certain sentences true, or

certain actions or attitudes good or rational, is, on this view, impossible.

It is the impossible attempt to

step outside our skins - the traditions, linguistic and other, within which we

do our thinking and self-criticism - and compare ourselves with something

absolute. (Rorty 1983, p. xix)

The attempt to represent the relation between

language and the world to determine if there is a correspondence is itself a

representation and, as such, needs justification from the outside. Rorty

objects to the attempt to use an empirical theory of the relation between

representations and the world as a foundation that will guarantee the

correspondence of our representations to the world. He says:

...

the issue is not adequacy of explanation of fact, but whether a practice of

justification can be given a "grounding" in fact. The question is not

whether human knowledge in fact has "foundations," but whether it

makes sense to suggest that it does - whether the idea of epistemic or moral

authority having a "ground" in nature is a coherent one. (Rorty 1979,

p. 178)

Rorty answers this question in the negative:

"... nothing counts as justification unless by reference to what we

already accept, and ... there is no way to get outside our beliefs and our

language so as to find some test other than coherence." (Rorty 1979, p.

178)

The Meaning of Life: Every particular

action or value can be questioned from some more objective point of view. Every

justification of any value is always from some other point of view which itself

needs justification. What we do now won't matter 100 years from now, and, even

if it did, what matters 100 years from now won't matter from some other point

of view. Every value requires external justification. All values that originate

from within a point of view cannot be objective and require external

justification. (See Nagel, 1986)

"That's Just your

Opinion":There

is no right answer, because every possible answer is just somebody's point of

view. That's just your opinion. (The implication being that simply because it

is an opinion from a particular perspective, it can't be objective or correct.)

Of course, simply calling these

arguments fallacious does not make them so. I will attempt to add some

argumentative sticks and stones to the name calling.

The first obvious problem with

the argument is that it seems to be a non

sequitur. It does not follow directly from the fact that a representation

is from a particular perspective that it cannot be objective. If 'objective'

means reflecting the object and not merely the subject, then the fact that a

representation is perspectival does seem to imply that it cannot be completely objective; but it does not

imply that it cannot be partially objective (i.e., that it reflect the object

in some of its properties or in some aspect of its form). The fact that a

photograph was taken from a particular place with a particular view of the object does not imply that none of

the properties of the photograph are due to, or reflect, the object and not the

point of view or the medium of representation. Most versions of the argument

simply do not follow unless one takes for granted a particular view of what

representations are and how they represent.

Most versions of the fallacy do

in fact take for granted a particular

view of representation and then proceed to show how objective knowledge is

impossible because of the very view of representation they assume. The second

problem with the Perspectivist Fallacy is that it implicitly assumes a very

dubious theory of representation without explicit argument. I call this view

the Physical Model of Representation, because it views mental and perspectival

representation as self-sufficient objects, using the way that physical

objects, such as pictures, can serve as representations as a model. To

understand most versions of the Perspectivist Fallacy we need to look briefly

at this view of representation and how it figures in the arguments of both the

weak and strong versions of the fallacy.

Imagine looking at an object and a physical representation of that object. Take, for example, a statue and the woman it was modelled after. In this case both the object and the representation are contained in the same perception. We perceive their similarities, and we can perceive the correspondences between the statue and the women. This allows us to see, for example, how the elbow of ivory maps onto the elbow of flesh. Thus we can take the ivory as representing the flesh; we project the properties of the woman onto the statue guided by the perceived similarities. The statue represents the woman only in virtue of the complete interpretation of the situation by the observer and the access that he has to both the statue and the woman. (Figure 2) This is a paradigmatic case of physical representation, but it is one that is bound to be incompletely analyzed. It is natural to leave out the part that the observer plays in this situation and attribute the representative qualities of the statue to its similarity to the woman. After all, it is the similarities that guide the projection of the properties of the woman onto the statue. The fact that this projection is an act of the observer, dependent upon his ability to interact perceptually with both the statue and the woman, is easily overlooked. It is this simplified analysis of physical representation that is taken as the paradigm and applied to mental representation.

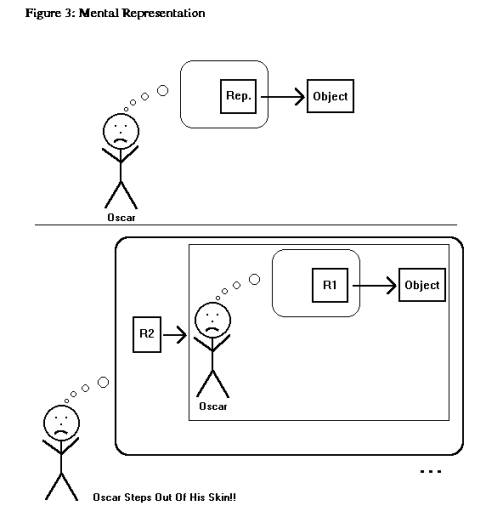

The

mental image (or the piece of language in modern theories) is seen as a

representation or picture. It is thought to function autonomously, apart from

the action of an interpreting subject and its interaction with an external

object, just as a physical representation seems to. The mental representation

is seen as a mental object that represents in virtue of its own properties.

Instead of seeing representation as a process of interaction between subject

and object and the perspective as the mode or manner in which this interaction

is carried out, the representation is reified into an object and the

perspective on the external world turned into a view of this mental object, not

a view of the external world. Through a

perspective we see only the reified representation not the world; thus,

perspectival representation becomes a veil of ideas separating the subject from

any independent access to the external object.

The

Perspectivist Fallacy is the argument that objective knowledge, and even

reference to external objects, are impossible on this view of

representation. This is completely

true. If we only have direct access to the representation and our internal

image is our experience of

the external object, this image cannot be compared to the external object

through some mind's eye that experiences both the image and the external

object. There is no way to ascertain the correspondence between internal

representation and external object. Every philosophical attempt to ascertain

the correspondence between representation and object can only issue in the

production of yet another mental representation, since all human knowledge is

from a perspective and perspectival knowledge is a view of a representation of

the world, not the world itself. (Figure 3) It is this view of representation

that is behind Rorty's claim that it is impossible to step outside of our skins

(our systems of representation) and that this is what is necessary in order to

have objective knowledge of the world:

It is the impossible attempt to step

outside our skins - the traditions, linguistic and other, within which we do

our thinking and self-criticism - and compare ourselves with something

absolute. (Rorty 1983, p. xix)

As we shall see, this is also the view of

representation that stands behind Berkeley's claim that a representation of an

external object is a contradiction in terms: What we see through perspectives

are mental objects, ideas, not external objects. Berkeley was one of the first

philosophers to realize that when see representations as mental objects without

any intrinsic connection to the external world, they no longer can serve their

representative function. He was the first to employ the strong version of the

perspectivist fallacy, to argue that representations from particular

perspectives cannot even represent or refer to external objects.

II

Berkeley's Argument

Let us look at how Berkeley's

argument involves this stronger version of the Perspectivist Fallacy. As

mentioned above, most interpreters (See Bennett 1971: pp. 137-142, Woolhouse

1988: pp. 118-119, and Jones 1969: pp. 287-288 for examples of this

interpretation and the criticism that follows it.) view the argument upon which

Berkeley was willing to stake the entire issue of the existence of material

objects as some instance of the following argument:

1.

Assume material objects exist, and try to conceive one existing without being

conceived in some thinkers mind.

2. In attempting to conceive a material object existing unconceived, you are

attempting to conceive something that is unconceived. This is a manifest

absurdity.

----------------------

By RAA, material objects don't exist.

They

then usually add this standard criticism of the argument: The argument makes

the obvious confusion between the properties of a concept and the properties of

what it refers to. In conceiving a mountain, I don't have rocks in my head.

Hence, in conceiving something unconceived, my concept is not unconceived, what

it refers to, the external object, is.

The contradiction disappears.

This interpretation and

criticism of the argument, however,

misses the essential point of the argument and its similarity to contemporary

arguments. The contradiction in conceiving a material object existing apart from

a perceiver does not simply lie in the fact that in conceiving of the object

you would become a perceiver of the object through which it would exist as an

idea. In the version of the argument that appears in Three Dialogues between

Hylas and Philonous (Berkeley 1962, pp. 183-192), Hylas is not convinced by

the argument given above and claims that the argument shows merely that we

cannot perceive material objects directly. Only ideas are perceived directly;

material objects are conceived only through the mediation of ideas that

represent external objects through their similarity to them. (Berkeley 1962, p.

187) Thus, although we cannot conceive them directly, Hylas argues that

external objects existing unperceived are at least possible (Berkeley 1962, p.

189). Philonous answers this by demonstrating that we cannot even represent

such objects mediately through our ideas, since our ideas can bear no

similarity to anything but an idea and material objects are by definition

unlike ideas. Berkeley's argument is really an argument that ideas in the mind

cannot even refer to or represent external objects and that, hence, all

attempted talk of external material objects "marks out either a direct

contradiction, or else nothing at all." (George Berkeley, Treatise Concerning

the Principles of Human Knowledge: I, 24. Berkeley 1962, p. 76) The

argument correctly interpreted is the following strong version of the

Perspectivist Fallacy:

The

key premise is the first. If representations are seen as mental objects and

perspectives are seen as views of representations rather than views of external

objects, then the representation can only serve as a representation, can only

refer to something, in virtue of some intrinsic property (similarity for

Berkeley). Berkeley was simply the first to see that if one takes what is

essentially an interaction between a subject and an object and turns it into a

reified entity that is separate from the object, it can no longer fulfill its

function as representing or referring to an external object.

III

Putnam's Version

Hilary Putnam has recently

advanced arguments against the view he calls Metaphysical Realism that have

exactly the same form as Berkeley's argument. They are also strong versions of

the Perspectivist Fallacy. They argue that it is impossible for representations

to represent or refer to external objects outside of the perspective or

conceptual scheme from which they originate. For Putnam, the problem is no

longer the impossibility of a similarity between mental ideas and extra-mental

reality, but the impossibility of independent access to the objects our

language is supposed to refer to or represent. He says in the Introduction to Realism

and Reason:

Early

philosophical psychologists - for example, Hume - pointed out that we do not literally

have the object in our minds. The mind never compares an image or word with an

object, but only with other images, words, beliefs, judgments, etc. The idea of

a comparison of words or mental representations with objects is a senseless

one. So how can a determinate correspondence between words or mental

representations and external objects ever be singled out? (Putnam 1983 p. viii)

Hence

any attempt to philosophically specify the relation between the representation and

the object is just another representation, whose relation to reality itself

needs to be specified. In his presidential address to the APA, "Realism

and Reason," he says:

The

problem, in a way, is traceable back to Occam. Occam introduced the idea that concepts

are (mental) particulars. If

concepts are particulars ('signs'), then any concept we may have of the relation between a sign and its object

is another sign. But it is

unintelligible, from my point of view, how the sort of relation the

metaphysical realist envisages as holding between a sign and its object can be

singled out either by holding up the sign itself ... or by holding up yet another sign... . (Putnam 1976, pp. 126-127)

The

problem is that any attempt to explain how reference is possible must fail

because it will only be more representation or theory. In particular Putnam

makes this argument against using a causal theory of reference to explain how

representation of external objects is possible. In "Realism and

Reason," he says, "Notice that a 'causal' theory of reference is not

(would not be) of any help here: for how 'causes' can uniquely refer is as much

of a puzzle as how 'cat' can, on the metaphysical realist picture."

(Putnam 1976, p.126) And in

"Models and Reality," he adds: "The problem is that adding to

our hypothetical formalized language of science a body of theory entitled

'Causal theory of reference' is just adding more theory." (Putnam 1977, p.18)

The argument, in the end, is the same as Berkeley's: Reference to external objects is impossible.

Try to imagine an account of reference to external objects. In doing so you are

not representing to yourself the reference relationship, but only a

representation or theory of it. Just as you cannot have a concept of a material

object that is not a concept, so you cannot have a theory of reference that is

not a theory.

IV

Conclusion

Both Berkeley's and Putnam's

version of the Perspectivist Fallacy show the strangely self-defeating nature

of the fallacy: Both arguments assume a

view of representation which the arguments that proceed from it show to be

mistaken. The strong version of the Perspectivist Fallacy shows that if

representations are taken as mental or linguistic objects that have no

intrinsic relation to the object they are supposed to represent or refer to,

and if perspectives are seen to be views of representations not interactions

with or relations to external objects, then representation or reference will be impossible. That is, representations

will not function as representations.

It is no surprise that when you

mistake a relation or interaction between two objects for a third object (and

this is the fundamental error involved in the Perspectivist Fallacy), you will

no longer be able to explain the relation in terms of this reified object. The

Perspectivist Fallacy is similar to reifying the interaction between a bat and

a ball (call it the bat-ball relation) and then arguing that it is impossible

to hit a baseball with a bat because

the bat-ball relation (now seen as an object, not a relation) must be

related to the bat and the ball by two other relations (the bat-(bat-ball

relation) relation and the

ball-(bat-ball relation) relation!) which must themselves be related to their

relata by third relations, which must themselves be related ... Of course, this

is also the similar to the third man argument, which analyzes the similarity

between two objects as yet another object, whose similarity to the first two

objects must itself be explained by another object, and so on. The

Perspectivist Fallacy assumes a model of representation that views the act

of representing as a reified object and, hence, makes reference and

representation impossible. It then goes

on to argue that reference to extra-mental objects is impossible. The

conclusion is not surprising, since the view of representation upon which the

argument is based is self-defeating.

The same holds of the view of objectivity of perspectival

knowledge involved in the weaker versions of the Perspectivist Fallacy. Objectivity requires that the representation

reflect the object and not the perspective from which the representation

arises. But since a perspective is seen as a view of the representation only

and not a relation to the object, every perspectival representation can reflect

or represent only another representation or perspective, not reality itself.

The attempt to justify our representations only results in more

representations.

Since any perspectival

representation is subjective, objectivity can only be reached by multiplying

the number of representations we have of an object in order to broaden our view

and to reduce the biasing influences of any one perspective. The aim is to

reduce the perspectival nature of our representation. To get a representation

that takes into account all views and is, hence, a view from nowhere in

particular. That this model of objectivity is self-defeating can be seen from

the following analogy:

The Amazing

Perspectivist Platform: Imagine a platform being built to reduce the amount of load

carried by any one of its supporting beams. In order to reduce the load carried

by any particular beam upon which the platform rests, the number of beams is

increased. Imagine also that as each beam that is added, we whittle a little

bit of wood off of all the beams, including the one we add. As more beams are

added the strength of each beam is decreased, but this is OK because the

portion of the load that each carries is also decreased as we add more. This

lessens the load on each beam and decreases the degree to which the platform

depends on each beam. The ideal limit of this process is obvious. As you add

more and more beams the width of the beams and the weight supported by each

will approach zero. This is an attempt to get a platform held up by so many

beams that it isn't held up by anything at all.

This

analogy makes clear the the fundamental incoherence involved in the view of

objectivity assumed by the Perspectivist Fallacy. It is an attempt to get a representation that does not reflect

any perspective or medium, a God's eye view. It is the attempt to get a

non-perspectival perspective, a representation that isn't a representation.

This is the project Rorty and Putnam criticize, and it is not surprising that

the project is impossible since it assumes a self-defeating model of

objectivity.

The analysis of the problems

involved in the Physical model of Representation are indeed correct. But they

should lead us to question this model of representation rather than to question

the possibility of reference and representational knowledge themselves. When a

view of representation implies that representation is impossible, it is time to

get a new theory of representation, not to conclude that representation is

really impossible. The Perspectivist Fallacy assumes, without argument, that a

certain view of representation is true and that certain conclusions about the

possibility of knowledge and reference then follow. I have tried to suggest

that the view of representation that is assumed mistakes what is essentially a

relation or interaction between the

subject and the object for a self-subsisting object. Even if I do not at

this time explain what a view of representation that did not make this mistake

would be like, the minimum conclusion that must be drawn from this analysis is

that it is incumbent upon those who employ the Perspectivist Fallacy to make

explicit the assumptions they are making about the nature of representation and

to defend them. The rhetorical point of the comparison to Berkeley was that

most contemporary proponents of the Perspectivist Fallacy would repudiate

Berkeley's version of the argument because they no longer share Berkeley's

assumptions about the nature of representation. Yet, their arguments are

directed at this view of representation and their general conclusions about the possibility of objective knowledge

and reference depend upon the assumption that this view of representation is

correct. My claim is that their arguments merely show that a Physical Model of

Representation is untenable, not that representation of external objects itself

is impossible.

The Perspectivist fallacy

ignores the possibility that representation is an act, not a property of a

physical object in isolation from a representer. To show that it is a fallacy I

need not demonstrate that such a view of representation is true; I need only

show that it is possible. If representing is an act in which we directly

interact with the world, particular perspectives must not only become bearers

of knowledge, but the foundations of all knowledge. Perspectives are not veils

of ideas, they are vistas onto the external world. Perspectives are not

windowless rooms from which there is no escape. They are themselves windows on

the world. They give a limited and incomplete view of the world, but a view

none the less.

REFERENCES

Bennett,

Jonathan. 1971. Locke, Berkeley, Hume: Central Themes. New York: Oxford

University Press, 1971.

Berkeley,

George. 1962. A Treatise Concerning

the Principles of Human Knowledge and Three Dialogues Between Hylas and

Philonous. Lasalle: Open Court, 1962.

Jones, W.T. 1969. A

History of Western Philosophy,Volume III: Hobbes to Hume (2cnd

edition). New York: Harcourt Brace

Jovanovich, Inc., 1969.

Nagel, Thomas. 1986. The

View from Nowhere. New York: Oxford University Press, 1986. See especially

Chapter XI, pp. 214-222.

Putnam,

Hilary. 1976. "Realism and

Reason." In Meaning and the Moral Sciences. London: Routledge and

Kegan Paul, 1978.

1977. "Models and Reality." In Realism and Reason. Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press, 1983, pp. 1-25.

1983. Realism and Reason. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1983.

Rorty,

Richard. 1979. Philosophy and the

Mirror of Nature. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1979.

1983. Consequences of Pragmatism. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press,

1983.

Woolhouse,

R.S. 1988. A History of Western Philosophy, Volume 5: The Empiricists.

New York: Oxford University Press, 1988.